It’s creative writing season again! (Isn’t it always?)

Young authors all over the greater Paris area are sharpening their pencils and collecting story nuggets in their writing journals in preparation for the:

2014 Young Authors’ Fiction Festival

co-sponsored by

Time Traveler Tours and the American Library in Paris.

The deadline for YAFF submissions is April 1st (no fooling!). Which means that many young Paris-based authors will have already moved beyond free writing. They may have committed to an idea that they are now drafting into a story, from beginning to middle to end. Or perhaps they have finished their first story draft and are ready to type it out on the computer, thus moving into the revising and editing stages.

If this is the case, they’re probably asking for some guidance right about now, either with the computing process or maybe they want feedback on the writing itself.

If you are wondering how to help your young author, or even if you can, then this post is for you!

Roaming Schoolhouse teachers in Paris conference one on one with their students in the revision and editing stages.

Can I, should I, help my young author?

The answer to this question is an unequivocal, “Yes.” It’s okay to offer guidance to your young author. Real working authors seek guidance all the time, from critique partners to agents and editors to family and friends. No writing can mature in isolation. So, please do feel free to help. However,

the key is to not do for your young authors,

but to guide them so that they may do for themselves.

Avoid the knee-jerk grab for the red pen (or any color pen for that matter). Don’t just correct the spelling errors; or tell them when their flow of ideas is illogical and should be moved around; or add whole sentences where thoughts may be missing. Instead, challenge yourself to make each call for support a Teachable Moment, that is, an opportunity for your young author to learn.

Meet them where they are in their own development as literate people, and move them forward from there, one step at a time.

And be ready to accept a “No” if your young author does not enjoy your point of view. The author gets final choice. End of story!

How should I help my Developing Reader/Writer?

Admittedly, guiding rather than doing is easier said than done, it also saves time to just do. So join me below as I unpack the writing process, by age and writing stage.

In this post, I suggest ways to guide our developing reader/writers.

I offer tips on how to steer pre-reader/writers through the creative writing process in this post.

And this post in the series is devoted to emerging reader/writers.

Developing Readers

It doesn’t take long for emerging readers to become developing readers. It’s more of a moment in the grand scheme of things, an Ah-Ha!

Once they’ve cracked the code, they’ve emerged. They begin to function independently as readers. And they embark on a much longer journey toward developing fluent literacy.

This stage continues over a longer period, throughout the school years and into university. It is characterized by increased comprehension and analytical understanding of text, as well as the ability to make meaning with more complex and sophisticated material.

As I stated in the two earlier posts in this series, language and literacy development begin with productive skills, and are followed by receptive ones: speaking follows listening; and writing follows reading. But the productive-receptive skill pairs reinforce each other too. Therefore, the more you can encourage your developing readers to write, they better readers (and writers) they will ultimately become.

Characteristics of developing writers

As writers, developing readers will tend to make fewer spelling errors than emerging readers. But as their ideas grow in sophistication, so do their story structures as well as their need to employ more complex grammar. Thus, logical organization and clear communication become the bigger challenges.

At this stage we see story plot lines becoming more complicated, and therefore more difficult to manage. Developing reader/writers may be adding subtle literary features, like metaphor, double meaning, satire, subplots, and moral messages, to their writing, all of which are reinforced by their increased capability as readers.

For all these reasons, when guiding young authors at this stage of development, it is still best to focus first on their meaning-making and only turn to the mechanics of writing – spelling, formatting, punctuation – in the fourth and final stage of the four-part process of story creation: Editing.

So, as you read their drafts and seek to guide them through the process of Revision, allow your feedback to be influenced by the following five questions:

Sarah offers OREO feedback to this young developing author in the midst of spinning a marvelous fantasy adventure.

1. What’s working? What do you appreciate about the story? Is it funny? Is it well organized? Does it hook you from the get go and pull you right in? Is the story problem clear? Does the end work to resolve the problem in a satisfying way? Does the middle include enough scenes to make the journey from beginning to end believable?

Something is always working well in any story draft. Focus in on that first so that you begin with positive feedback.

Let your young authors know what you like about their stories before you move into more critical territory. In this way, their confidence will be preserved and your help becomes a Teachable Moment.

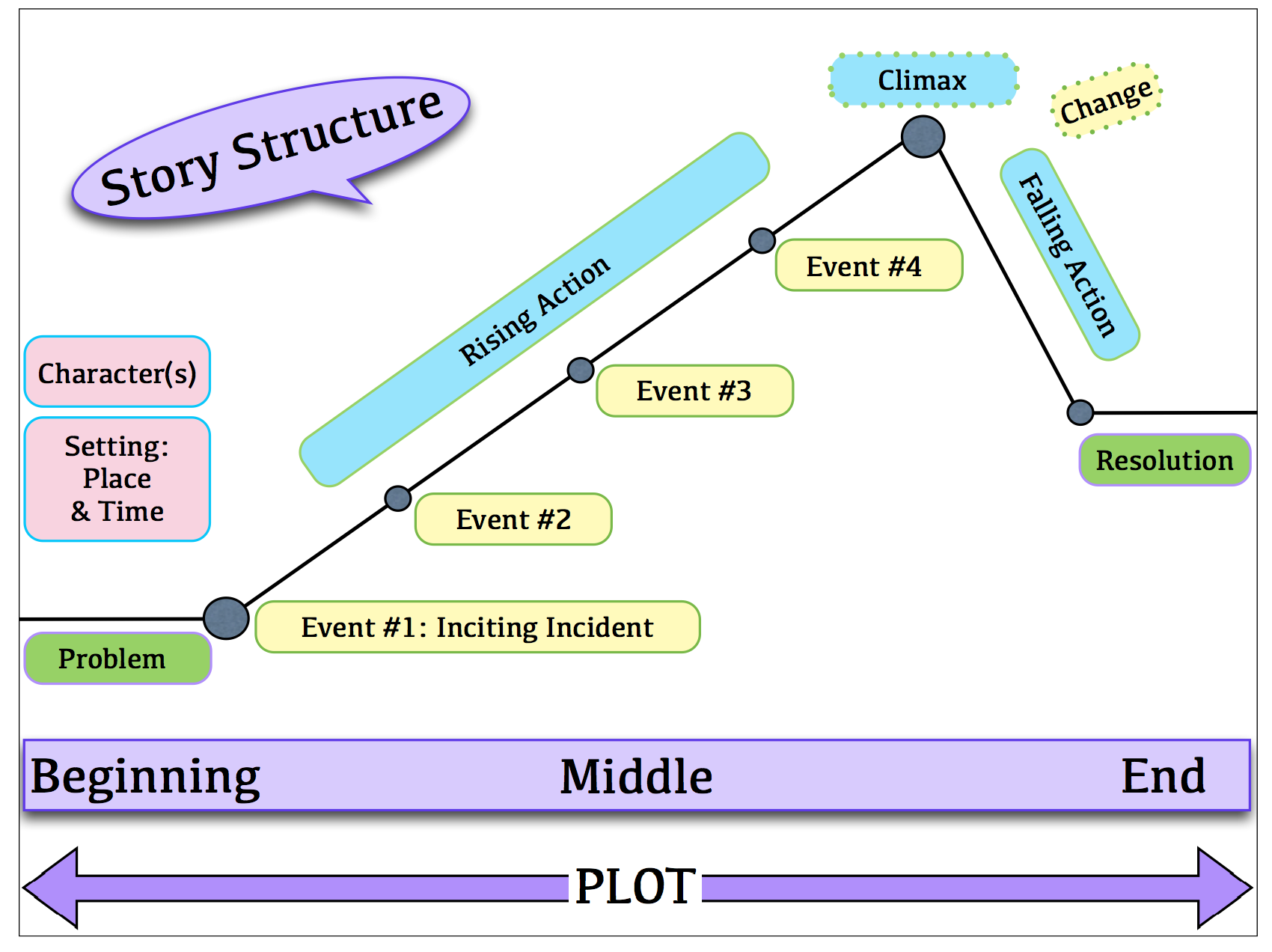

2. What’s missing? All stories follow a similar structure. There must be a beginning, middle, and an end.

The beginning communicates the story problem. It will also introduce the main character and offer a sense of place and time. But if there’s no problem, there’s no story.

The end provides the resolution to the problem.

The middle traces the main character’s journey from problem to resolution in a series of scenes, or events. It will also include the obstacles or additional dilemmas or challenges the character must overcome en route to the story resolution, or simply the stops taken or friends made along the way. These events will tend to rise in intensity or suspense or hope or lack thereof, culminating in a climax event. In the climax, everything will come together and a change or transformation will take place, usually in the main character.

Copyright 2014 Sarah Towle

If any of these elements – the beginning, middle, or end – is missing in your young author’s story draft, that's a great place to begin revising.

Ensure that the story problem is established in the first quarter of the story. Then look to see if the problem is resolved (and not simply by waking up from a dream). Verify that the middle has enough events, presented in a logical sequence, that tie the problem and the resolution together.

Some authors will draft great beginnings, but never get to the end. Others will get the beginning and end down, but the middle may be lacking and need fleshing out. Others knock out the journey, climax, and resolution, but have to go back to paint the problem a bit more clearly.

Even experienced adult authors have to face these challenges. So there is no shame in going back and revising one’s story from the initial draft. Often several times!

I recommend at least three revisions for every story draft at this stage.

3. What’s not in the right place? Is the problem stated in the first quarter of the story, or buried in the halfway point? If the latter, move it.

Does the journey move from point A to B to C? Or does it leap to B, back into A, then zig to D before zagging to C? Rearrange it.

Stories are linear. They therefore follow the rules of logic and cause and effect. But young authors can often run ahead before they’ve paved the road. Your comments should guide them to mix and pour the cement with just the right amount of water, gravel, and sand added.

4. What’s not needed? All writers overwrite at the drafting stage. In the process of getting the draft out, we include bits that don't ultimately serve the story. Or we take several sentences to communicate what could be said in one. Or we string together long grammatical structures when a simple declarative sentence will suffice.

Less is always more. And it’s actually more difficult to be concise.

So once your young authors have completed a full story draft, help them to see which pieces, if any, really don't belong.

It can be great practice for young authors to learn to focus on the essentials. Especially when there is a word limit (as in the YAFF).

5. What’s confusing? Of course, nothing is ever confusing to the author. We see the entire story in our heads. So our writing is clear as California pool water to us.

But questions from a careful reader are a signal to an author that, in fact, we haven’t done our job as well as we thought.

Teach your young author, therefore, that questions are good; that they usually indicate where revision is necessary. These are the places they need to rework in order to clear up any confusion.

Example: A character refuses to play his guitar at the family picnic in one scene because of a broken string. Then, in the next he's practicing. How is that possible? Did he get a new string? Where? When? Or is he only playing with only five? How does that sound?

This is the kind of thing I’m talking about. And they are easy fixes. Young authors just need help sometimes to see them.

One Final Tip!

The above questions will not only guide you in helping your young authors. They can also be employed by young authors to help each other!

That’s right. This is a great age, and stage, to teach your young authors the value of offering encouraging critical feedback such as I’ve described it above.

I call it OREO Feedback (like the cookie).

It works like this:

Start with something tasty and sweet: What you like; what’s working well.

Then move to the gooey-not-so-sure-about filling: What’s Missing? Confusing? Not needed? Etc.

Finally, end with another something yummy and easy to digest, comments like: It’s such a great idea, I wish I thought of it! Keep going. This is going to be a great story!